General Overview

On average approximately 10,400 North American children (between birth and 14 years of age) develop childhood cancer each year and these numbers seemingly increase annually1.

More than 80% of these children will be long term survivors who have been cured of their disease. This was very different 20 to 30 years ago, when the majority of children did not survive their disease.2

In general, cure rates have been improved by using:

- Multiple treatment modalities:

- Chemotherapy

- Surgery

- Radiation therapy (RT)

- Therapy intensification (using higher total doses of chemotherapy over a shorter period of time)3

- Improved supportive care

Though this approach has improved disease free survival, it has become obvious over the past 10 to 20 years that survivors of childhood cancer are at risk for many significant long term health risks or “late effects”4 as a result of this treatment.

Late effects are generally classified as side effects that occur more than 5 years after diagnosis - though there is debate about this definition. For example, acute myeloid leukemia (AML) related to Etoposide therapy often occurs within 3 years of therapy and is a treatment related side effect.

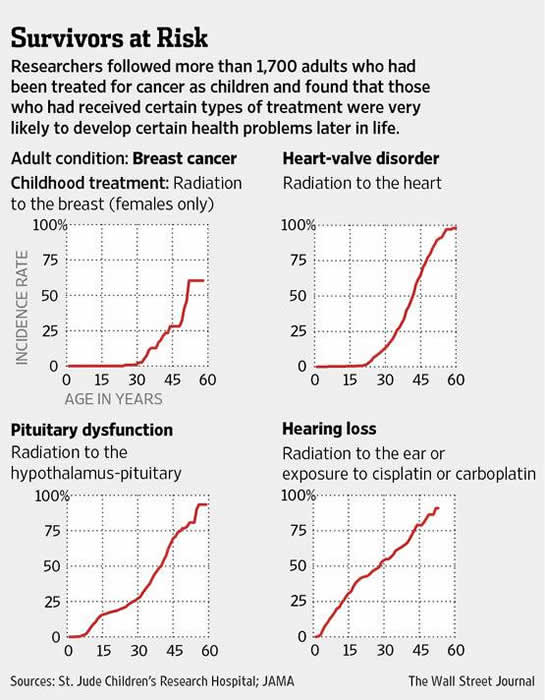

It was previously estimated that two thirds of survivors have at least one chronic health problem related to their previous cancer therapy and up to one third of these late effects would be major, serious or life threatening.5 However, a recent study from St. Jude Children's Research Hospital published in JAMA showed that these health problems are more common:

They recalled and assessed just over 1700 adult childhood cancer survivors and found that at age 45 years, there was a:

- 95.5% cumulative prevalence of any chronic health condition

- 80.5% cumulative prevalence for a serious/disabling or life-threatening chronic condition

This study also showed that the risk of long-term health problems in cancer survivors increases with time from therapy.

These health risks vary in severity, but can affect every body system and may have significant impact on the survivor’s quality of life. For example: Radiation therapy (RT) is associated with an increased risk of second cancers many years after treatment. Chemotherapy agents such as alkylating agents are associated with infertility and second cancers. Anthracyclines are associated with cardiomyopathy.6

Early detection, prevention, and interventions to treat some of these complications provide the opportunity to reduce cancer-related morbidity and mortality.7

The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) has developed guidelines for the screening and management of late effects at: http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org/

These guidelines were developed using expert opinion consensus and by reviewing the current literature.

The COG advocates a “risk based strategy” which involves a personalized plan for long term screening depending on:

- The type of previous cancer

- The type of cancer therapy given

- Genetic predispositions

- Life style behaviors

- Other co-morbidities8

Uncertainty regarding some of these guidelines revolves around ongoing changes in pediatric cancer therapy, the long latency period of many treatment related late effects, the multiple factors known to influence cancer-related health risks and the unknown effect of patient aging.

In general terms, the severity of long-term side effects depends on:

- Treatment intensity

- The combination of cytotoxic agents (for example chemotherapy can sensitize normal tissues to RT and increase the risk of damage)

- The age of the child at the time of treatment

- Underlying patient factors such as genetics

Common problems experienced by the survivors of childhood cancer include:

- Reduced growth and development

- Organ damage (such as kidney, heart and lungs)

- Endocrine problems (such as hypothyroidism and growth hormone deficiency)

- Infertility

- Increased risk of developing a second malignant neoplasm (SMN)

This resource will explore the more common health problems which affect survivors of childhood cancer and aims to be an easily accessible source of information for health care practitioners.

Development of the late effects section was made possible by a grant from the University of British Columbia Teaching and Learning Enhancement Fund.