Informed Consent

Emergencies

A person may be unable to give consent due to a variety of factors such as

- Mental impairment

- unconsciousness

- Extreme illness

Somebody in a major road traffic accident may need life saving therapy and is in no position to give consent.

Viewed as an implied consent - patient would have given consent if they had been in a position to. Necessity justifies therapy.

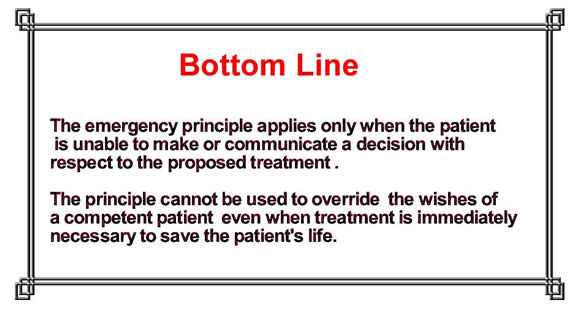

There are limitations however:

Necessary versus convenient:

Canadian courts differentiate between a procedure that is "necessary" as opposed to one that is "convenient."

Consent is expendable if the procedure or treatment is immediately required to save life or preserve health. Consent is required on all other occasions.

Necessary Procedure:

Marshall v Curry:The doctor discovered a grossly diseased testicle in the course of a hernia repair operation. He removed the testicle because he judged it to be potentially gangrenous and therefore a threat to life but also because it was necessary to do so to complete the hernia repair. The patient was under anesthetic and so there was no consent. Afterwards the patient sued him for battery.

The court justified the doctors actions in an emergency on "the higher ground of duty." When a great emergency which could not be anticipated arises, a doctor can act without consent in order to save the life or preserve the health of a patient.

Full text of CMAJ article about Marshall v Curry from 1935

Un-necessary Procedure:

Murray v McMurchy: A doctor tied a patient`s fallopian tube because he discovered fibroid tumors in the uterine wall during a Caesarian section and was concerned about the hazards of another pregnancy. He was held liable for battery. The trial judge held that while it was convenient to carry out the procedure at that time, it was not necessary. The tumors were not an immediate threat to the patient`s life or health.

Advance Directive:

The application of an emergency doctrine is limited if the patient while competent made his or her wishes known with respect to treatment (advanced directive or living will).

See also Malette v Shulman (1990), 67 D.L.R. (4th) 321 (Ont. C.A.). This case is described in the battery page of the overview section.